Print This Article

2018 Best Practice - CPE Opportunity!

Use of Multimodal Analgesia in Women Post-Cesarean Section: From Innovation to Bedside

by submitting author: Zahra Khudeira, PharmD, MA, BCPS, CPPS co authors: Ashleigh Swearingen, MD; Carlos Sandoval, MD; Lelas Shamaileh, P4; Noha Mohamed, P4; Serene Abuzir, P4; Alexander Frank, MS

Objectives:

- Describe the multimodal analgesic approach

- Recognize the advantages of the multimodal approach

Pain management has received extra attention over the past few years as the opioid epidemic was declared a major healthcare issue in the United States. The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) reported that over 42,000 Americans died due to opioid overdose in 2016, an average of 115 people per day, with about 40% of these deaths resulting from prescription opioids.1,2 Opioids come with a multitude of side effects, including but not limited to nausea, vomiting, constipation, fatigue, pruritus, and life-threatening respiratory depression. With dependence, patients experience tolerance to the drug’s analgesic action, increased sensitivity to pain, and hyperalgesia.3 Notwithstanding, opioids have been instrumental in improving the lives of countless patients. Before opioids were regularly prescribed, many patients’ pain was not being adequately controlled, subsequently impacting mobility – which in and of itself causes many health complications – and quality of life. With all this in mind, healthcare professionals are on a mission to devise strategies for adequate pain control while minimizing opiate dependence and its consequences.

Surgery is controlled trauma. It is common practice to prescribe opioids for the treatment of acute pain following surgery, such as a cesarean section (C-section). Controlling pain in the post-cesarean patient population is particularly important because the immobility caused by the pain further increases these women’s risk for thromboembolic events beyond their already increased baseline risk. Additionally, uncontrolled pain may negatively affect mother-baby bonding and can increase risk for postpartum depression and anxiety.4-6 While opioids are still the most common form of postoperative analgesia in this patient population, many institutions are looking for other treatment modalities that will minimize opiate use to avoid their associated complications.

In 2016, the American Pain Society (APS) worked with the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) to develop guidelines for postoperative pain management.7 These guidelines strongly recommend multimodal analgesia for postoperative pain management in adults and children, which they define as “the use of a variety of analgesic medications and techniques that target different mechanisms of action in the peripheral and/or central nervous system (that) might have additive or synergistic effects.” Furthermore, the guidelines recommend scheduling around-the-clock non-opioid analgesics, explaining that this practice may not only decrease the likelihood of long-term opiate use and its associated risks/complications, but it can also offer superior pain relief versus opiates alone.

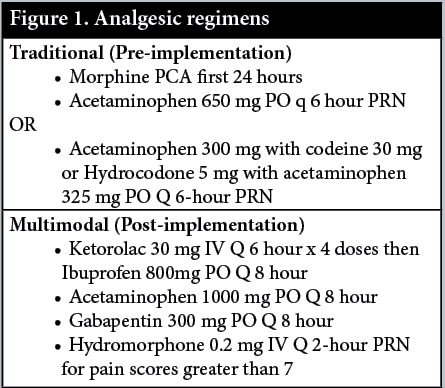

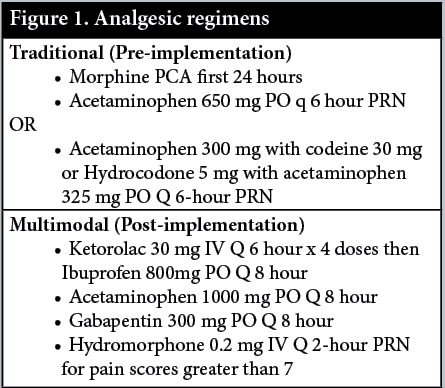

Mount Sinai Hospital’s labor and delivery unit underwent a paradigm shift in analgesic practice. The traditional opioid and as needed-based regimen was revamped to the multimodal approach (Figure 1). Before implementing this multimodal analgesic approach to post-C-section patients, the labor and delivery unit was utilizing patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) with morphine for the first 24 hours after cesarean delivery followed by oral acetaminophen with hydrocodone or codeine. Additionally, women were often discharged from the hospital with opioid prescriptions. After implementing multimodal analgesia, the new physician order set included the following non-opioid medications: ketorolac (a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug), acetaminophen, and gabapentin. Hydromorphone was incorporated into a patient’s pain management when she reported a pain score of at least 7 on a 10-point scale. The goals with this multimodal approach were to standardize post-cesarean analgesia in a way that minimized opiate use while still maintaining pain control immediately postpartum and at discharge. Other endpoints of the study included length of hospital stay and overall patient satisfaction. Unfortunately, there is limited information regarding multimodal analgesia specifically in the C-section patient population. Thus, this study contributes to the discussion of multimodal analgesia by providing perspective into the use of this technique in this specific patient population.

The current postoperative pain management strategy is a multimodal approach described as simultaneous use of analgesics with different mechanisms of action for an additive and synergistic effect, but also with fewer side effects.7 Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and acetaminophen work together to provide anti-inflammatory and antipyretic relief, reducing visceral pain originating from the uterus. Gabapentin offers a synergistic effect mediating neuropathic pain. The multimodal approach reduces opioid requirements and the subsequent adverse effects while simultaneously increasing pain relief via modification of signal transmission throughout the pain pathway.

Description of Program

The multidisciplinary team that worked on this multimodal approach and studied its outcomes included obstetrics/gynecology physicians, nurses, pharmacists, medical students, pharmacy students and a statistician. Our labor and delivery unit serves a high-risk population in collaboration with the Level III Neonatal Intensive Care Unit delivering an average of 160 babies per month. There are 28 attending OB/GYN physicians and 16 OB/GYN medical residents. There are at least 2 attending physicians and 2 residents available 24 hours/day. We care for high-risk women who may be dependent on illegal substances, have multiple comorbidities, and often do not receive routine prenatal care nor take their prenatal vitamins.

Our team met regularly to discuss barriers to implementation and ensure success of the program. The initiative went live November 27, 2017. The current order set was revised to reflect all changes. The core research team submitted an Institutional Review Board (IRB) application to analyze the effectiveness of the new analgesia modality. The IRB-approved study focuses on two time periods, pre-implementation and post-implementation of multimodal analgesia. The pre-intervention period was September through November 2016 and post-intervention period was January through March 2018.

The study design was a retrospective chart review. The patients were identified from historical discharges through the electronic medical record. Inclusion criteria were C-Section patients aged 18 to 46 years old who received PCAs or multimodal analgesia post-operatively.

Exclusion criteria included:

- Most or all pain scores missing in patient charts

- Patient delivered both vaginally and c/s for same pregnancy (twins)

- Vaginal delivery

- Intrauterine fetal death (IUFD) delivery

- Patients that are unable to receive NSAIDs or opiates (contraindication)

An unpaired t-test 2-tailed with heteroscedasticity (unequal variance) for each variable was utilized to determine the p-values.

Data collection included:

- Age

- Weight/Body mass index (BMI)

- Parity and number of prior C-sections

- Length of stay (date and time of admission and discharge)

- Allergies

- Inpatient post-operative analgesia (including route, dose and date/time of administration)

- Pre- and post-pain scores

- Discharge medications

Experience with and outcomes of the program

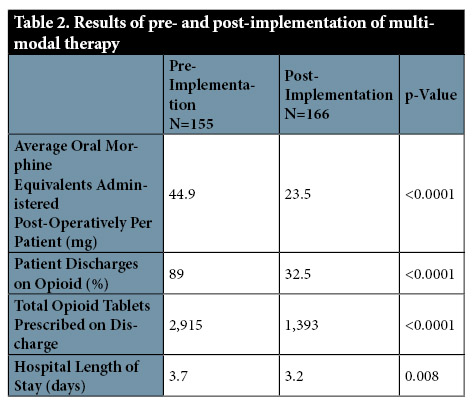

The implementation of multimodal analgesia to C-Section patients involved a paradigm shift, with a goal of standardizing analgesia in post-operative C-Section patients and reducing length of stay as well as opioid use. The impetus for this change in practice was threefold. First, nurses reported a time delay in receiving PCA pumps from central supplies, meaning women may already have pain before the PCA began. Second, the clinical team wanted to reduce the use of opioids with a model similar to the Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) protocol by utilizing multimodal analgesia, which has been successfully employed in gynecological patients. Third, we wanted to improve patient satisfaction by allowing patients to ambulate earlier after surgery. The admission and post-operative analgesia order sets were updated. The changes were positively embraced by most of the healthcare professionals on the Labor and Delivery and Mother Baby Units. After implementing this new technique, women are ambulating hours after the C-Section; Foley catheters are discontinued, and diets are advanced sooner; and most importantly, patients are being discharged from the hospital on average after 3.2 days.

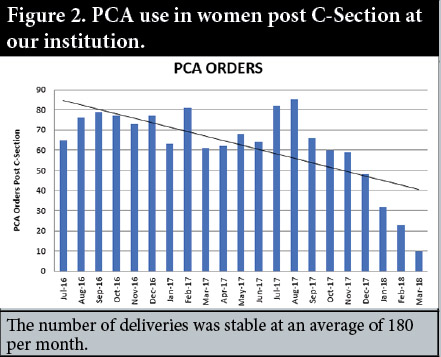

After the implementation of the multimodal order set, the use of PCAs significantly decreased (Figure 2). There were many obstacles to using PCAs including obtaining the pump from central supply department in a timely manner, ensuring the pump is programmed correctly, providing adequate patient education, documentation of medication infused, standardized nurse documentation per shift, consistent documentation of pain scores into the medical record, etc.

Discussion of innovative aspects of programs and achievement of goals

The United States has the highest rate of opioid consumption in the world. We consume 99% of the world's supply of hydrocodone and 81% of the world's supply of oxycodone.8 Physicians have a remarkable ability to combat this epidemic directly by decreasing the number of opioids provided. Patients are more prone to continue long-term opioid use after taking them for just 5 consecutive days.1 Thus, when treating acute pain, using multimodal therapy is ideal to achieve the lowest effective dose of immediate-release opioids for the shortest duration possible, if an opioid is necessary at all. Three days are often sufficient, and more than 7 days is rarely needed.

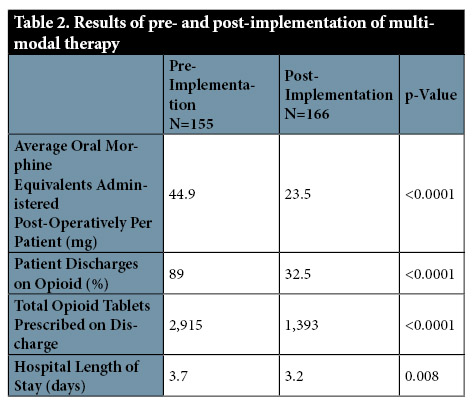

Our efforts to minimize opioid use both during hospitalization and upon discharge proved to be successful. After analyzing our data (Tables 1 and 2), we found that the calculated inpatient oral morphine equivalents for the pre- and post-intervention groups were significantly less in the multimodal group, decreasing from 44.9 mg pre-implementation to 23.5 mg post-implementation. As expected, the PCA utilization dropped dramatically. Although multimodal analgesia for women undergoing a C-section has generally been well-received at our institution, some private practice obstetricians may have continued to use their preferred analgesia, which may explain why there was still some PCA use.

Our data revealed 89% of post-cesarean patients were discharged home with narcotics from October to November 2016. In the post implementation period, the percentage of women discharged with opioids was 32.5. The opioid pill burden was reduced by 52%. We successfully reduced the opioid prescriptions and number of tablets circulating in the community from 2,915 to 1,393 tablets quarterly.

Opioids and their related adverse events threaten patient safety, lead to prolonged hospital stays, and increase the economic burden to hospital systems.6,11-13 Targeting high-risk patients for non-opioid pain management strategies, including locally acting, non-systemic medications and surgical interventions, may reduce opioid requirements. We encouraged the use of adjuvant medications to target specific types of pain and reduce opioid use. Post-implementation of multimodal analgesia data shows that the current length of stay is 0.5 days less (p= 0.008). This translates to a projected annual savings of $4.8 million based on the average cost of stay per day for patients who underwent cesarean deliveries. Our standards for acceptable pain control prior to discharge have remained unchanged from 2016 to 2018. The patients tend to be more satisfied since they are mobile and can go home sooner. Patient education was a significant source of this change. The patients were extensively educated about post-operative pain expectations after discharge from the hospital and given careful instruction on how to continue their medications for optimal pain control.

Although the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) Practice Alert states that opioids may be administered by the patient-controlled intravenous route, we have found several limitations and barriers to this practice, including time required to obtain a pump from central supplies and incomplete nurse documentation in the medical record. Based on the challenges of PCAs and the advantages of multimodal analgesia, our hospital decided to forgo PCAs and utilize scheduled NSAIDs and acetaminophen in combination with gabapentin.

We encountered a few limitations with this retrospective analysis. First, the amount of opioids that the patients received from PCAs was difficult to ascertain. The nursing documentation for opioids infused was often lacking or misrepresented. We theorized the entire 50 mg was utilized if there was no documentation of wasted opioid volume. Therefore, we may have overestimated the use of opioids in the pre- and post-implementation phase, if the patient received a PCA.

The retrospective research highlighted areas for improvement including the documentation of post pain scores by nurses. Four patients without documented BMIs were excluded from analysis. Removal of codeine from updated order sets was a collateral benefit. Codeine can be ultra-metabolized in some women which produces higher plasma levels leading to more pronounced respiratory depression in breastfeeding neonates.

Conclusion

Healthcare is a complex system and is ever-increasing with value-based purchasing. Healthcare organizations are being asked to deliver better, more efficient care with fewer resources. Healthcare providers must recognize the impact that pain can have on patients’ health as well as quality of life and advance efforts to improve pain management.14

For a successful implementation of a new initiative, the key stakeholders should be at the decision table. There should be camaraderie, mutual respect and accountability for each task. Once implemented, the program needs to be reviewed and revised as necessary. Our initiative underwent a Plan, Do, Study, Act format. The practice change was successful, and our future goal is to expand multimodal analgesia to other surgeries.

Multimodal analgesia comprises of two or more medications with different mechanisms of action to produce a synergistic or additive analgesic effect and fewer overall adverse effects. The United Sates is dealing with an ongoing crisis of prescription opioid abuse, therefore the practice of prescribing non-opioid analgesics is desired.7 APS, ASA and CDC guidelines encourage the use of multimodal analgesia.1,7 The use of multimodal analgesia and the initiation of oral medications as quickly as possible after surgery can decrease length of hospital stay and, therefore, decrease health care costs and lower patients’ adverse event risks.16-17 ■

References

- Centers for Disease Control, 2017.

- About the U.S. Opioid Epidemic. HHS. 2018. Available at: https://www.hhs.gov/opioids/about-the-epidemic/index.html.

- Benyamin R et al: Opioid complications and side effects. Pain Physician 2008 11:S105-S120.

- Kerai S, Saxena KN, Taneja B. Post-caesarean analgesia: What is new? Indian Journal of Anaesthesia. 2017;61(3):200-214.

- Gadsden J, Hart S, Santos AC. Post-cesarean delivery analgesia. Anesth Analg. 2005;101:S62–S69.

- Apfelbaum JL, Chen C, Mehta SS et al. Postoperative pain experience: results from a national survey suggest postoperative pain continues to be undermanaged. Anesth Analg.2003; 97:534-40.

- Chou R, Gordon DB, Leon-Casasola OA, et al. Management of postoperative pain: A clinical practice guideline from the American Pain Society, the American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine, and the American Society of Anesthesiologists’ Committee on Regional Anesthesia, executive committee, and administrative council. J Pain. 2016;17(2):131-157.

- Gomes T, Tadrous M, Mamdani MM, Paterson JM, Juurlink DN. The Burden of Opioid-Related Mortality in the United States. JAMA Network Open. 2018;1(2):e180217. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.0217

- The Joint Commission. R3 Report Issue 11: Pain Assessment and Management Standards for Hospitals; 2018.

- The Joint Commission. Sentinel Event Alert: Safe Use of Opioids in Hospitals. 2012; issue 49.

- Carr DB, Goudas LC. Acute pain. Lancet. 1999; 353:2051-8.

- Shafi S, Collinsworth AW, Copeland LA, et al. Association of Opioid-Related Adverse Drug Events With Clinical and Cost Outcomes Among Surgical Patients in a Large

- Oderda GM, Said Q, Evans RS et al. Opioid-related adverse drug events in surgical hospitalizations: impact on costs and length of stay. Ann Pharmacother. 2007; 41:400-7.

- Bohnert et al: Association between opioid prescribing patterns and opioid overdose-related deaths. JAMA, April 6, 2011;305(13):1315-1321.

- Buckley B. Data mining can improve opioid safety. Pharmacy Practice News November 2012, volume 39.

- Kehlet H, Dahl JB. The value of "multimodal" or "balanced analgesia" in postoperative pain treatment. AnesthAnalg. 1993; 77:1048-56.

- Kehlet H, Holte K. Effect of postoperative analgesia on surgical outcome. Br J Anaesth.2001; 87:62-72.

The 2017 ICHP Best Practice Award is supported by PharMEDium-AmerisourceBergen.